Tomorrow, I’ll take part in the SheBuilds Hackathon from Lovable. Before jumping into building anything, I wanted to slow down for a moment and document how I’m preparing for it.

Writing helps me a lot when I’m working through a problem. It helps me organize my ideas, prioritize them and see where I should focus first and what the logical next steps are.

This time is no different. Before the Hackathon starts, I want to make my thinking explicit: how I’m defining the problem, how I plan to validate it, and how I’m setting myself up to use the limited time in the best possible way.

Context

I’ve been an expat for many years, living in different countries. Whenever I move to a new city, I usually join expat and newcomer communities to understand how the city works, discover events, and learn from other people’s experiences.

Over time, I started noticing a very clear pattern.

Across Facebook groups, WhatsApp chats, Telegram groups, and similar communities, the same type of question keeps appearing again and again: Does anyone know someone trustworthy to help me with <put your everyday task here>?

Sometimes it’s about home cleaning or small repairs. Other times it’s about childcare, pet care, or looking after your home while being away. These messages are everywhere, and they repeat constantly.

Occasionally, someone replies with something like: “I know someone who cleans for a friend and she’s very happy, but I’m not sure if she has availability.” The information is scattered and most of the time, it gets lost quickly in long chat threads where people talk about many different things.

What’s interesting is that people keep asking these questions even though platforms, apps, and agencies already exist. The fact that they still rely on private groups and personal connections suggests that existing solutions are not fully solving the problem.

People are looking for an extra layer of reassurance. Asking within a community of people who share something in common adds a form of validation before trusting someone enough to let them into their home or care for something important.

At the same time, even these group-based solutions often fall short. Answers are incomplete, outdated, or disappear quickly, leaving many people without a clear solution.

This repeated pattern made it clear to me that there is a real, unresolved problem here. That realization was the starting point of the idea I submitted for the SheBuilds Hackathon.

Beyond the practical need, I’m also deeply interested in a broader question: in a world where digital tools are everywhere, how can we recreate trust that normally grows between people through shared experiences and common connections?

This Hackathon is a great opportunity to explore that question more intentionally.

The problem I want to explore

Based on these repeated observations, the core issue is not a lack of services or people willing to help. There are many people available to clean homes, fix things, care for children or pets, or help with everyday tasks.

The real problem appears at the moment of choosing. At its core, this is a question of trust. How do you decide to let a stranger into your home, or trust them with something that matters to you?

This challenge is especially relevant for people who have recently moved to a new city. They still need to work, manage personal commitments, handle family responsibilities, and in many cases take care of pets. Getting help is not a “nice to have”; it’s a real need in order to make daily life work.

What I’ve noticed is that, in response to this uncertainty, many people turn to community-based groups to look for recommendations. There seems to be a very human instinct at play: if someone I share something in common with has had a good experience with a person, there’s a higher chance that I will too.

However, existing options often force people to choose between:

- paying to access platforms without knowing if they will actually find someone suitable

- relying on anonymous reviews that are hard to verify

- or scrolling through informal group chats where recommendations are fragmented and quickly outdated

As a result, many people delay getting help or settle for options they are not fully comfortable with.

This is the problem I want to explore during the Hackathon:

how people make trust-based decisions in a new city, and what is currently missing to help them feel confident when choosing someone for everyday support.

Early assumptions

From these observations and conversations, I’ve started to form a few early assumptions. At this stage, they are not conclusions, but working hypotheses that I want to validate.

The first and most important assumption is that this is not a supply problem. There are many people offering childcare, pet care, cleaning, repairs, or general help. The real question people are asking themselves is: can I trust this person?

Behind that question, there are very real concerns.

Will this person treat my child well?

Will they take good care of my pet?

Can I leave my home alone while they are inside?

Will they respect my space and my belongings?

These doubts appear again and again, especially when someone has no local references to rely on.

A second pattern I’ve noticed is that people tend to follow one of two paths.

Some look for recommendations inside expat or newcomer communities. Being part of a shared group seems to create an extra layer of reassurance. If someone with a similar background or situation has had a good experience, it feels safer to trust that recommendation.

Others decide to go the “professional” route and contact agencies that offer cleaning, childcare, or home services. These services often feel safer at first because there is a company behind them, which creates a perceived barrier and a sense of accountability.

However, my assumption is that many people are not fully comfortable with these services either. From what I’ve heard, these relationships often feel transactional and rigid. Services are strictly defined, extra requests come with additional costs, and there is little room to build a personal relationship or long-term trust.

In many cases, the person helping in the home is not incentivized to go beyond the minimum required, which makes it harder to establish the kind of trust that people actually need when they invite someone into their private space.

Another assumption is that trust grows more naturally when there is continuity, shared context, and social validation, rather than one-off transactions or anonymous reviews.

I also want to check if having access to a public profile of the candidate could help build trust. It allows people to verify that a person exists and that recommendations and experiences shared by others refer to the same individual.

All of these assumptions point in the same direction: people are not just looking for help. They are looking for ways to reduce risk and feel confident in their choices.

The goal of the next step is to test whether these assumptions hold true beyond my own experience and conversations.

How I plan to validate the problem

At this stage, my goal is twofold: to check whether my assumptions are valid, and to stay open to problems I may not have considered yet.

I see this phase as product discovery. It’s about understanding how people currently deal with this situation, where they struggle, what feels hardest, and what often goes wrong when they try to find help in a new city.

Rather than looking for confirmation only, I want to create space for unexpected input that can challenge my initial thinking and allow for better product decisions during the Hackathon.

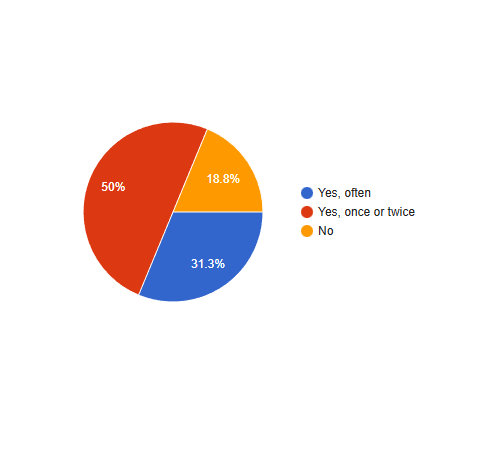

To do this, I decided to start with a simple survey. The survey is designed to help me answer a few key questions:

- How often do people face this situation?

- Where do they go today when they need help?

- What part of the process feels most frustrating?

- What makes them hesitate or feel uncomfortable?

- What matters most to them when choosing someone?

Designing the survey

When designing the survey, my main goal was to keep it short and easy to answer.

I wanted to respect people’s time while still collecting information that would be useful for decision-making during the Hackathon. Rather than asking everything, I focused on asking the right things.

I structured the survey in a few clear blocks, each with a specific purpose.

First, I wanted to understand the context: whether people had actually looked for this kind of help before, and how often.

Next, I focused on current behaviour. I wanted to learn where people go today when they need help and which channels they rely on, whether that’s private platforms, agencies, or community groups.

I then moved into experience and frustration. This part is about identifying where the process breaks down and what causes the most discomfort or stress.

A dedicated section focuses on trust. Here, the goal is to understand what makes people feel comfortable trusting someone they don’t know yet, and what matters most when making that decision.

I’m also curious to understand what people do after the first contact. Whether they call, video chat, or meet in person, these steps often reveal how people try to reduce uncertainty before trusting someone.

Finally, I included open-ended questions. These are especially important, as they allow people to describe real experiences in their own words and often reveal problems or needs that structured answers can miss.

Here you can find the latest version of the survey.

Distribution plan

Once the survey is ready, the next step is making sure it reaches the right people, at the right time.

Over the past days, I’ve also been gathering input in a less structured way. I’ve been talking to friends and acquaintances who have lived abroad, moved cities within the same country, or are currently expats. Many of these conversations happened informally, over coffee, on the phone, or even at a Christmas market in Vienna. These discussions helped me better understand how people describe the problem in their own words and what tends to frustrate them most.

In parallel, my plan is to start distributing the survey on Sunday, sharing it in selected WhatsApp groups and newcomer communities where these questions already come up regularly.

On Monday morning, a few hours before the Hackathon officially starts, I plan to publish a LinkedIn post with more context and a link to the survey. This allows me to reach a broader audience while clearly explaining why I’m collecting this information and how it connects to the Hackathon.

When it came to tools, I considered a few options, including Typeform and Google Forms. Given the time constraints, I decided to use Google Forms.

Preparing for execution

Beyond problem discovery and validation, I also want to be intentional about how I execute during the Hackathon.

With limited time, the tools and support system I choose can make a big difference. My goal is to focus my energy on thinking, building, and learning, rather than setting things up.

For this Hackathon, I plan to rely on a small set of tools I already know well:

- Lovable, both for building the prototype and using its built-in chat to iterate quickly

- ChatGPT, as a thinking partner for product decisions, writing, and structure

- Claude and Gemini, to get alternative perspectives and avoid tunnel vision

I’m deliberately avoiding adding too many new tools. Familiarity and speed matter more than experimentation at this stage.

In parallel, I’ve also reached out to people in my network. I plan to lean on other Product Managers in my circle to get quick feedback, challenge my assumptions, and help me spot blind spots I might be missing.

Having external perspectives can be incredibly valuable during a fast-paced build. It helps me step back and make better decisions without overthinking.

What comes next

Tomorrow, the Hackathon starts.

The first step will be reviewing early survey responses and using them to define a clear scope for the MVP. From there, I’ll move into building a simple prototype in Lovable.

This experiment will continue over the next few days, focusing on learning, decisions, and execution under time constraints.

Leave a comment